Batteries conceal something truly magical: a store of energy that can be used as electricity. What was a source of amazement 200 years ago when Alessandro Volta unveiled his first battery – the voltaic pile – has become something we take for granted today. Flexible energy storage is an essential aspect of smartphones, laptops, and vehicles – and at the very core of the energy transition. But the wishlist of attributes for the ideal battery is still long: cheaper, safer, more powerful and durable, free from harmful materials, and easy to recycle. Through their research work, the experts at e-conversion are addressing these challenges and taking batteries to the next level.

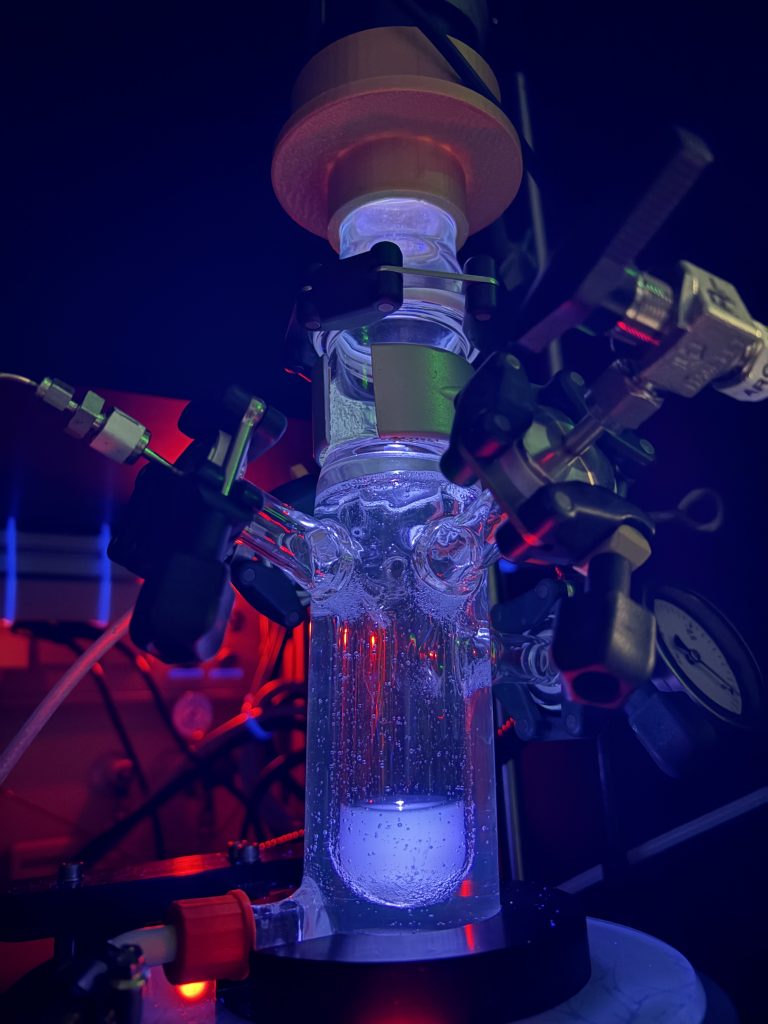

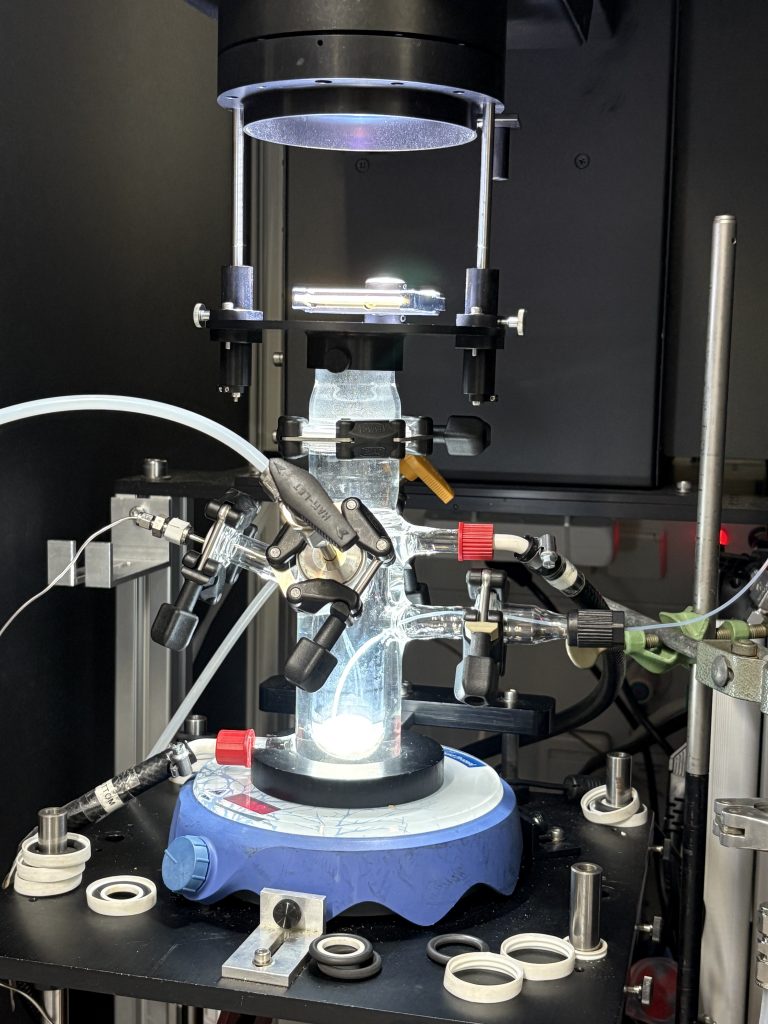

Storing the sun: Prof. Bettina Lotsch and her team at the Max Planck Institute for Solid State Research in Stuttgart are developing materials for solar batteries that can store solar energy for hours and later use, over many charging and discharging cycles. (Photo: Julia Knapp / MPI-FKF)

Green power is an unreliable companion – dependable when the sun is shining or the wind blowing, but faithless when neither is available. For renewable energies to become a dependable partner, energy storage capacity needs to be massively expanded, because Germany has set itself an ambitious climate target: it aims to be greenhouse gas neutral by 2045. And there are target milestones along the way: renewables are to be increased to 80 percent of gross energy consumption by 2030. High-performance energy storage devices are key to achieving the climate goal because they compensate for fluctuating energy generation from renewables and help make green power available on demand. Meanwhile it will be important to continue promoting wind farms, solar plants, and climate-friendly mobility. “This goes to show how finding a durable way to store an electric charge is fundamental to the whole transformation process. Not forgetting the transition from fossil to electricity-based industry,” comments Jennifer L.M. Rupp. She is Professor of Solid-State Electrolyte Chemistry at TU Munich, Scientific Director of TUMint.Energy Research GmbH, and e-conversion 2.0 coordinator from January 2026. “The fact is the way we currently transform energy using wind and solar power is based on just fifty materials, most of which were invented and developed in the 1970s. We need a new generation of innovative materials for the energy transition 2.0 – a Green Energy Tech revolution, no less,” declares the material scientist and founder of the start-up Qkera (see interview with co-founder Dr. Andreas Weis).

Rethinking battery research

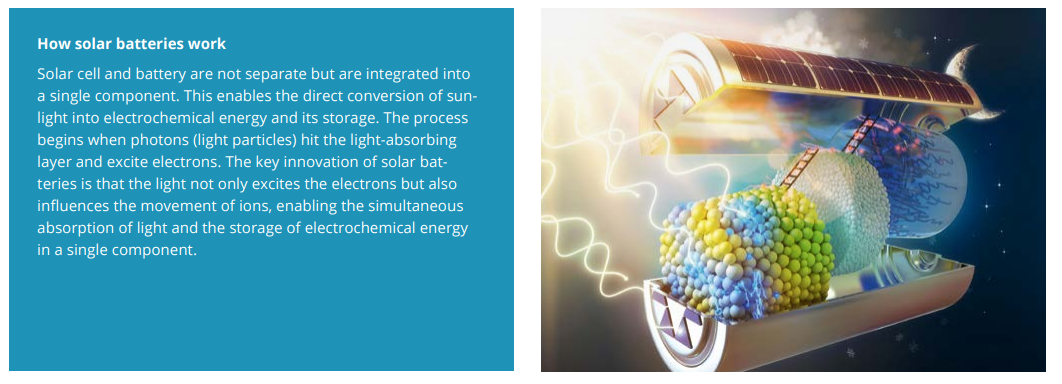

There are plenty of innovative ideas lined up – and the researchers at the e-conversion Cluster of Excellence are pioneering the discovery of new material candidates, stepping up research into the most promising candidates, and designing entirely new battery concepts. “For instance, we’re working on technologies to bridge the gap between energy conversion and storage. This could include direct light storage systems,” explains Bettina V. Lotsch, Director of the Max Planck Institute for Solid State Research and honorary professor at LMU Munich. “To translate such new concepts into devices, here at the Cluster of Excellence we bring together experts from a wide range of disciplines such as material chemistry, optoelectronics, photovoltaics, and battery research,” says the material scientist, who will also join the e-conversion 2.0 team of coordinators from January 2026.

Driving the Green Energy Tech revolution – that’s the goal Prof. Jennifer Rupp is consistently focused on. She investigates solid-state materials and how they can be used as functional components in energy conversion and storage systems. (Photo: V. Hiendl/e-conversion)

Storage technologies: the backbone of the energy transition

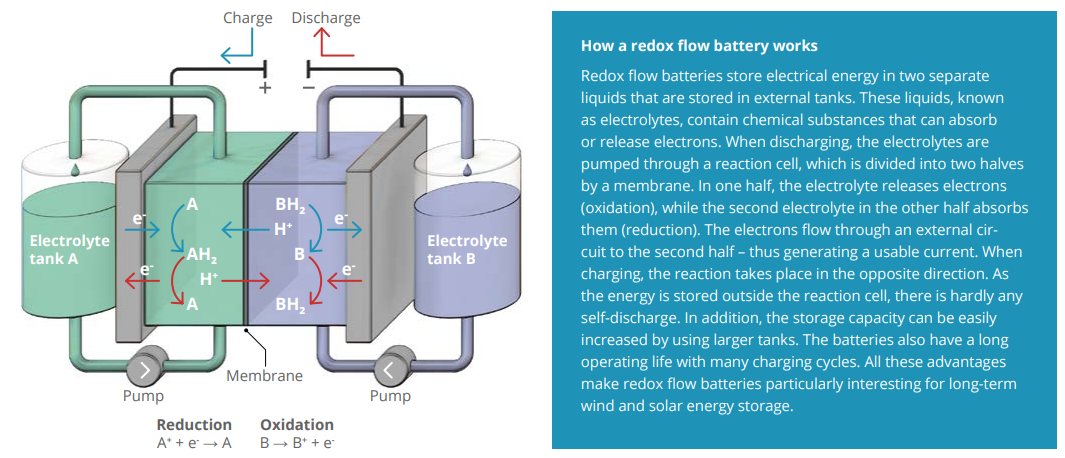

Anyone who has looked at the options for energy storage will have quickly realized that the components feature a vast array of technologies, designs, and materials – and demand continues to grow. “Batteries are the backbone of green electrification. But they need to become more efficient, more sustainable, and cheaper if they are to meet the rising demand for storage capacity,” adds Rupp. “How can this be achieved? What are the innovative energy conversion and storage concepts? Which mechanisms are critical? What are the most promising materials or material combinations for solutions 10 to 20 years hence? These are some fundamental issues that are the very essence of what we’re doing at e-conversion.” The chemist is researching solid-state materials and how they might be used as functional components for energy conversion and storage concepts. Rupp and her team are also working on the development of innovative lithium solid-state conductors and low-cost synthesis pathways for new hybrid and solid-state cells. Their aim is to create high-performance batteries with a higher energy density, but suitable for low-cost manufacturing at scale. The expert from TU Munich and her team are also looking at another technology for addressing the challenge of energy storage: sustainable redox flow batteries (see infographic at the end). Such batteries are especially good at storing high amounts of energy, making them an efficient way to hold surplus wind and solar energy for later use.

Revolution with redox flow batteries

Redox flow batteries feature two different liquid electrolyte circuits. The liquids converge in two reaction chambers that are separated by a membrane and house the electrodes. There the electrolytes exchange ions and generate a flow of usable current. During charging the system absorbs energy, at the electrodes the reactions are reversed and the system stores electric current. The special characteristic of these batteries is that the electrolyte tanks – and therefore storage capacity – can be freely scaled up, independently of the electrodes’ areas. Such electrochemical energy storage systems have previously depended on vanadium, however, a costly and environmentally harmful metal with a volatile supply. “We are therefore doing research into a cheaper, more sustainable alternative – redox flow batteries based on iron compounds, which are a readily available, low-cost waste product of the steel industry,” explains Rupp. The membranes also play a key role because they are responsible for charge transport between the electrolytes. Conventional systems use polymers. Their drawbacks are their operating life and cost. “That is why we are developing ceramic materials that are more robust, efficient, and environment-friendly,” says Rupp, who aims to bring the concept into industrial operation in partnership with Prof. Fikile Brushett at MIT (Massachusetts Institute of Technology).

New materials and new ideas

The TU Munich expert sees interdisciplinary research partnerships as a vital source of inspiration and the e-conversion community as an enriching opportunity. “That inspires me to keep exploring new paths. We are working in close partnership with Prof. Thomas Bein’s research team at LMU Munich, for example. They have developed a covalent organic framework that could be a very useful material for pioneering energy storage devices,” continues Rupp. “That material is special because it can act as both anode and cathode. We and our groups have used it to develop a bipolar electrochemical storage system.” It consists of a single, uniform electrode material, with one side serving as the anode and the other as the cathode. The advantage is a simpler construction using sustainable materials.

Research power in a new light

Another research approach at e-conversion is exploring a completely new storage concept: the convergence of solar and battery technology. TU Munich and the Max Planck Society recently pooled their research power in establishing the MPG TUM SolBat Center, the world’s first Center for Solar Batteries and Optoionic Technologies – with the support of the Bavarian Ministry for Economic Affairs, which is providing eight million euros in funding. The center’s activities focus on solar batteries, which are still largely unexplored and are therefore intensively investigated by e-conversion expert Bettina Lotsch and her team. “Solar batteries combine solar cells and batteries in a single component and can store the energy from sunlight directly in electrochemical form – and then release it again as electrical energy,” explains Lotsch, who was awarded the 2025 Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Prize for her outstanding work in thefield of materials chemistry. The SolBat Center is the brainchild of Prof. Bettina Lotsch, Prof. Jennifer Rupp, and Prof. Karsten Reuter (FHI Berlin) and conducts research into optoionics, an emerging interdisciplinary field of research at the intersection of optoelectronics and solid-state ionics that investigates how to control ions using light. “Improving light-controlled processes in energy materials is one area of focus, along with creating newtypes of energy systems at the interface of batteries and photovoltaics. There could be immense potential in direct light storage devices for various solar and optical applications,” adds the Max Planck scientist.

Ingenious scaffold molecules: Together with her team, Prof. Bettina Lotsch has developed a material that can store sunlight for up to 48 hours, allowing the captured energy to be used later. (Photo: J. Otto/DFG)

Solar batteries: a double benefit

Her team, which extensively researches the conversion of sunlight into chemical energy by photocatalysis, came across the idea of creating a solar battery (see infographic at the end) with optoionic materials while conducting an entirely different experiment: the research team had come up with a very promising material and wanted to find out whether it behaved like a typical solar cell in exciting just electrons – or whether the incident light also set ions into motion, as in a battery. “An experiment revealed that the yellow material turned blue under irradiation with visible light,” explains Lotsch. “The exciting discovery was that when the light source was turned off, the blue color persisted for quite some time – a phenomenon that could be linked to the optoionic storage of solar energy.” Since then the chemist has kept coming back to this serendipitous discovery, one of her research highlights, because this kind of optoionic material has potential for a dual function: energy generation from sunlight and the storage of solar energy.

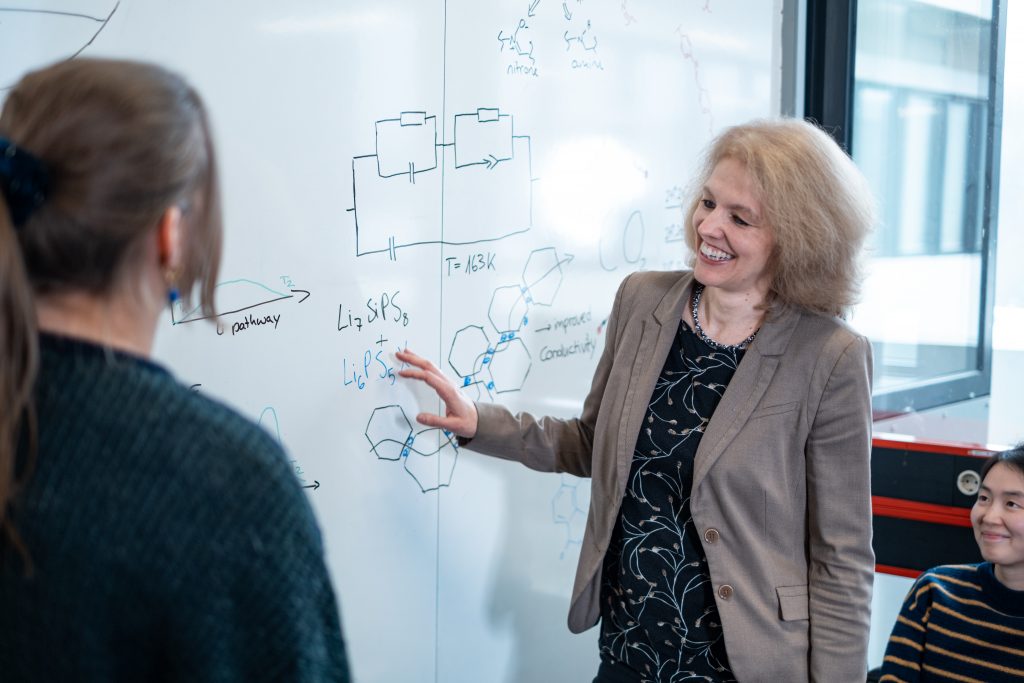

Captured electrons: How materials can be charged with light (left) and which conditions must be present in the solid-state lattice are key questions which are being investigated by Prof. Bettina Lotsch (right) at the Max Planck Institute in Stuttgart. Her team hopes to use this knowledge to find new material candidates for the emerging research field of optoionic storage materials. (Photo: J. Knapp/MPI FKF)

Caging light energy

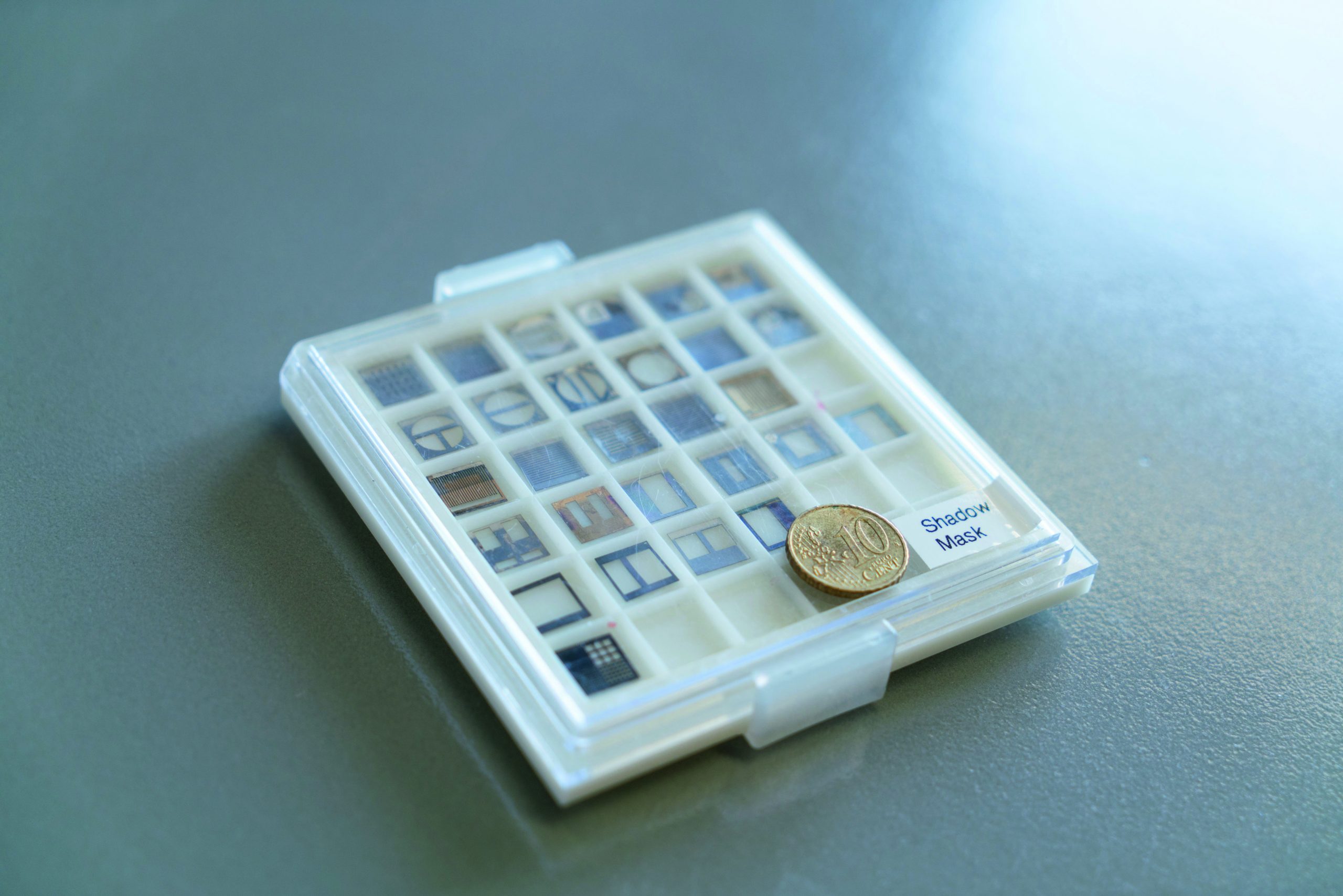

Her team has now developed such a bifunctional cell. It has the same structure as a conventional battery with an anode, cathode, and electrolyte. The difference is a thin layer of a two-dimensional carbon nitride as photoanode that incorporates potassium ions. The crucial process takes place in that material. “When its color changes we see that electronic charge carriers are formed,” she explains. “Light-induced electrons accumulate in the carbon nitride layer as they are screened by the potassium ions. As such, they prevent the charge carriers from reacting and allow the electrons to accumulate – a process we call photocharging.” The system can be charged like a battery – using light as its energy source. Lotsch and her team, together with researchers from TU Munich and the University of Stuttgart recently increased the scope of optoionic materials further: They developed a new organic framework material known as COF (short for covalent organic framework) that captures sunlight and stores its energy for 48 hours. Again, the material combines the functions of a solar cell and a battery in a single system. Thanks to its high performance and stability, it can supply power even after the sun has set – without the need for rare or critical elements.

A new branch of research: optoionic materials

But the top priority for Lotsch and her team is to identify the fundamental mechanisms at work in such materials. How does charging with light work in different optoionic materials? How relevant is the composition and structure of the material? Which ingredients are needed for electrons to accumulate? These questions, and others, are what the researchers are seeking to answer in order to use that knowledge to develop new candidates for the emerging research field of optoionic materials. TU Munich researcher Rupp, who leads the SolBat Center together with Lotsch and Prof. Karsten Reuter, Director of the Fritz Haber Institute in Berlin, is confident: “The combination of solar and battery technologies will open up a new dimension in pioneering a sustainable energy supply. The concept of this globally unique center is based on the close integration of basic research and technology development. We see it as an opportunity to create much more compact and efficient energy systems.”

What scope is there to get even more from the battery materials? Hubert Gasteiger, Professor of Technical Electrochemistry at the Technical University of Munich, is addressing these and other questions. Among other things, the chemical engineer and his team are developing new battery materials for lithium-ion, sodium-ion, and solid-state batteries. (Photo: V. Hiendl/e-conversion)

The limits of lithium-ion batteries

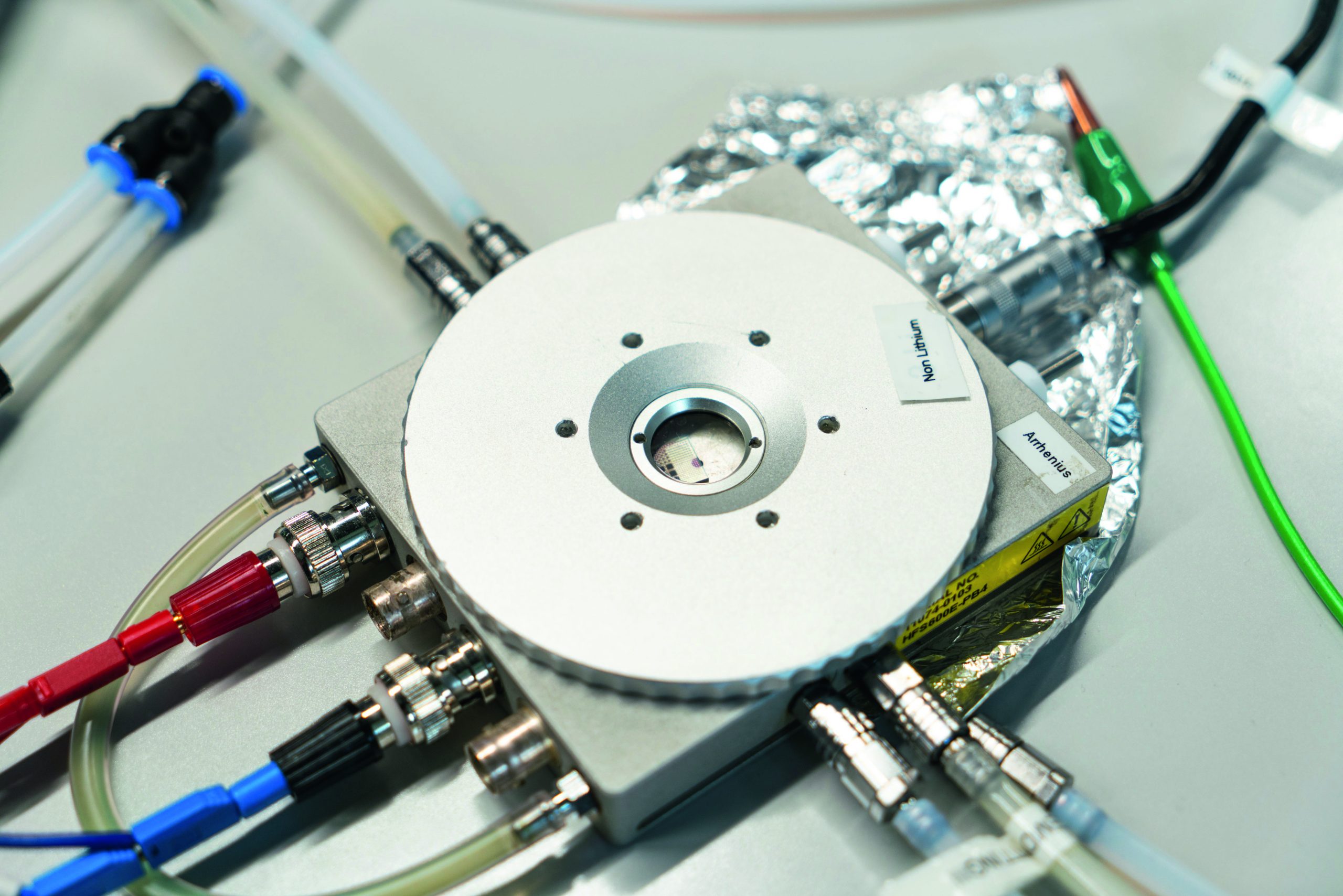

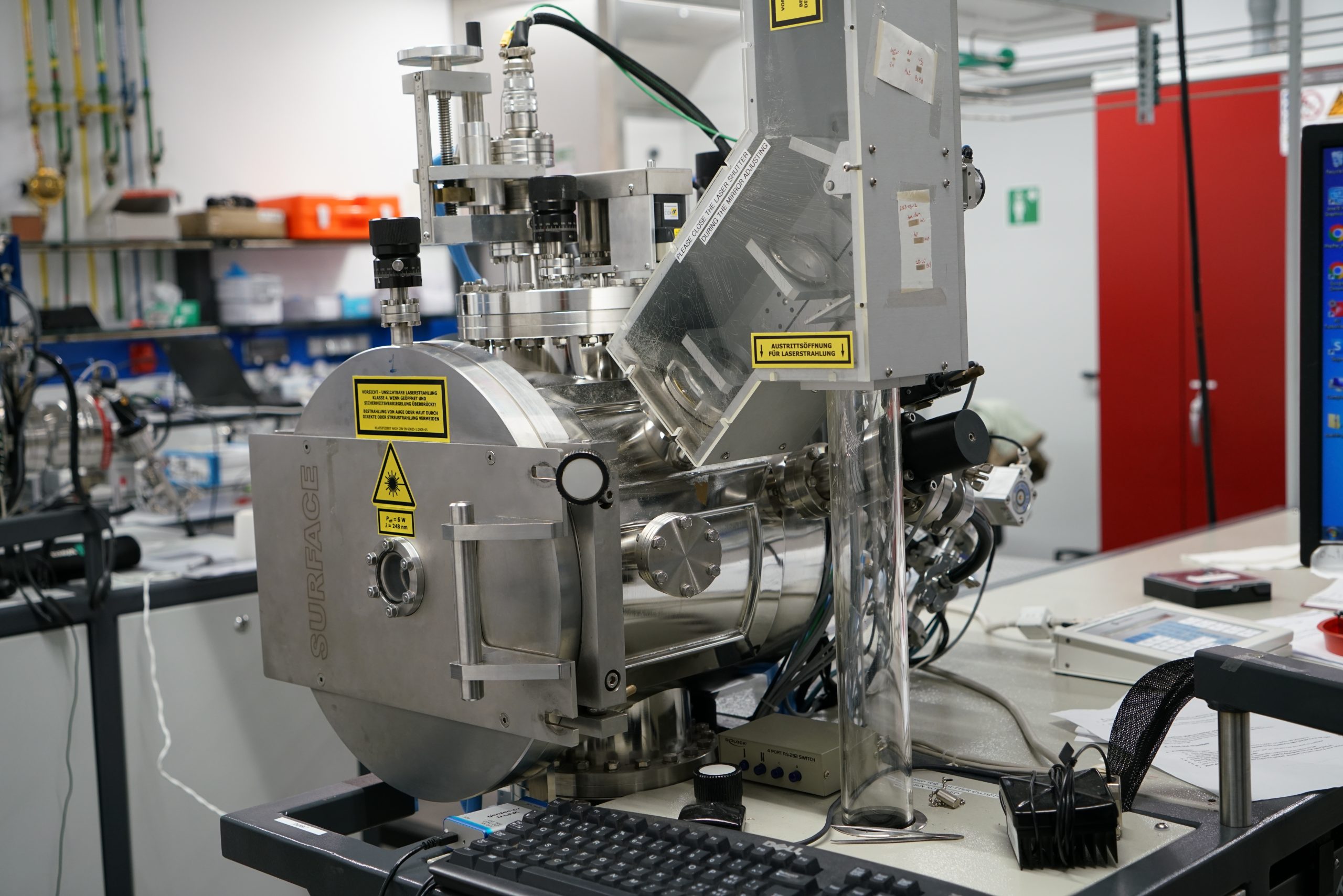

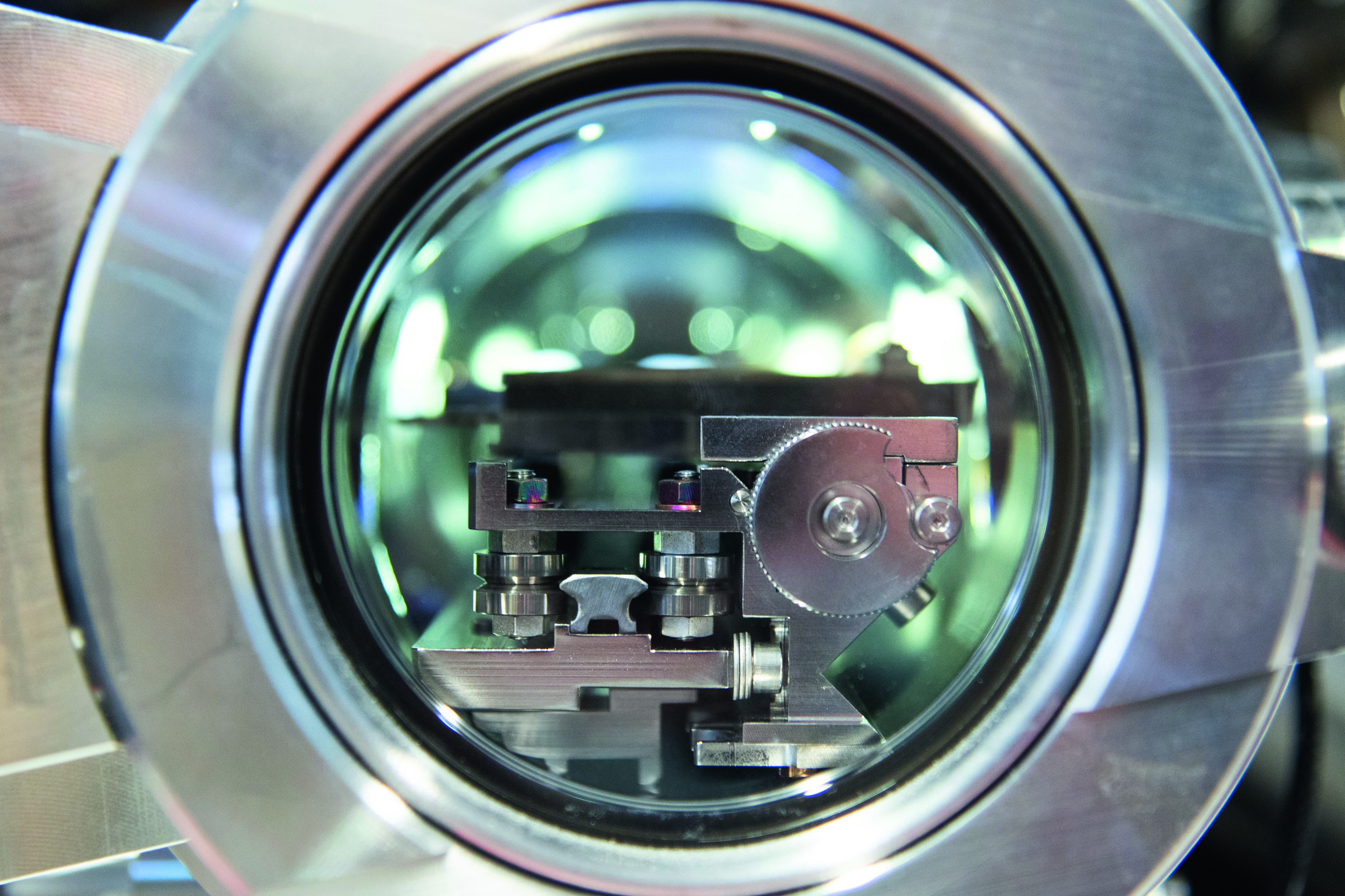

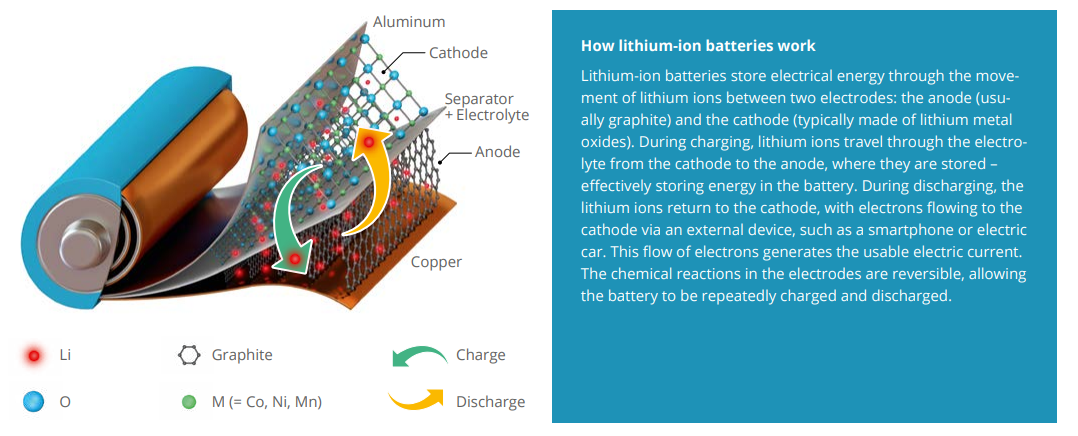

While solar batteries are still at the basic research stage, lithium-ion batteries can already boast a brilliant research career. This mainstay of electric mobility has undergone a remarkable transformation. The first lithium-ion batteries that came on the market in the early 1990s were heavyweights with relatively little energy storage capacity. The versions we encounter today are slimline high-tech devices. The difference in performance between then and now is like comparing a steam engine to a jet engine. The impressive development of lithium-ion batteries highlights just how efficient modern batteries already are. But they need to become even better, in other words energy-richer, safer, cheaper, more durable, and more sustainable. So where are their limits? What scope is there to get even more from the materials? That is what preoccupies Hubert Gasteiger, Professor of Technical Electrochemistry at TU Munich. The work of the chemical engineer and his team includes the development of new battery materials for lithium-ion, sodium-ion, and solid-state batteries. “We want to understand how new materials affect the battery cells and how durable they are. That puts us at the interface of basic research and applied research with industry-relevant cells,” comments Gasteiger. “We employ a range of characterization methods in our work in order to understand the fundamental ageing processes.” That, especially, plays an important part in boosting the energy density of lithium-ion batteries. “In trying to increase their performance even further, we’re effectively pushing the materials to the limits of their stability,” explains the expert from TU Munich. “Identifying those limits and how they affect durability and safety is one focus of our research work.”

Why there’s a catch to more energy

Quite often, this is a balancing act, because one way to increase the energy density of lithium-ion batteries (see infographic at the end) involves progressively delithiating the active materials in the positive electrode by raising the potential. Because in every cycle of charging and discharging, lithium ions move between the electrodes and store electric current or release it again. That makes it such a game changer if the electrodes – the anode (negative) and cathode (positive) – can store and release lithium ions reversibly. “Storing more energy in a battery means more lithium ions need to be extracted from the cathode active material during charging and stored in the anode. The maximum amount of retrievable ions dictates the battery’s capacity,” explains Gasteiger. “But that makes the material thermodynamically more unstable – at the expense of safety and operating life.” The higher the voltage applied and the more rapid the charging processes, the faster the cathode material and electrolyte age.

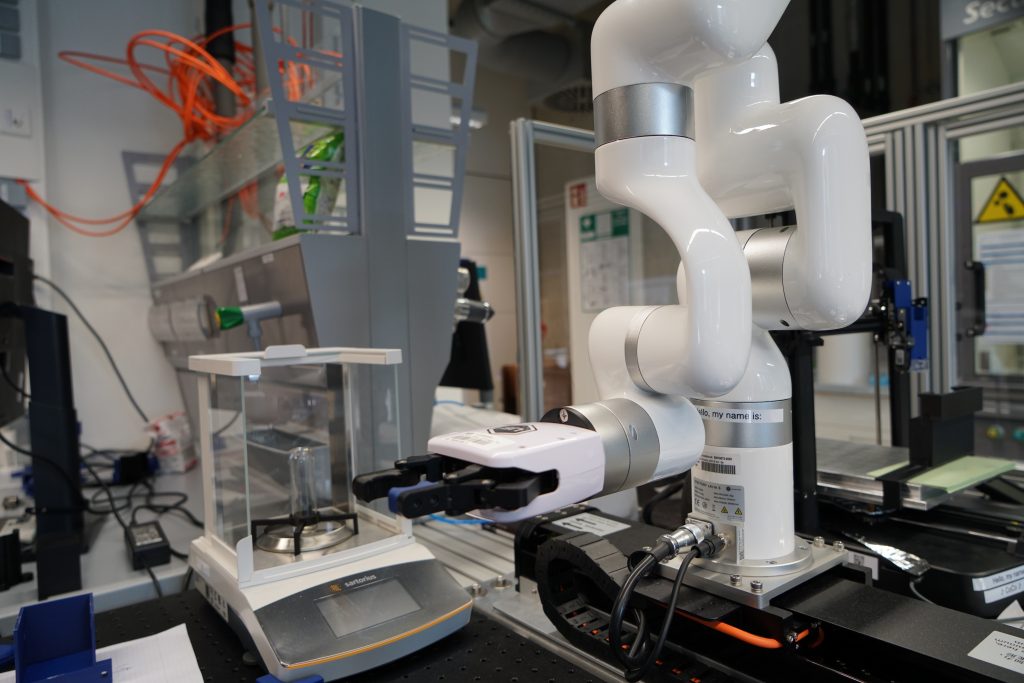

New battery materials in record time

In tracking down promising new material candidates much faster and specifically optimizing them, researchers increasingly employ a combination of automated platforms, artificial intelligence (AI), advanced simulations, and robotics. Material experts firmly believe such technologies can bring on a paradigm shift in research practice. One pioneer in this field is e-conversion researcher Helge Sören Stein, Professor of Digital Catalysis at TU Munich. “Instead of spending years testing individual components, we use a platform that directly optimizes the entire system,” remarks the physicist and doctor of mechanical engineering, who has specialized in automated research systems. “This way we can now uncover trends in material composition that would otherwise take years of work in the lab,” explains Helge Stein. His research brings together a range of disciplines, from chemistry and physics to engineering and IT. The basis of his work is the Materials Acceleration Platform (MAP), which he believes will significantly speed up material development. Stein’s team has been instrumental in developing and implementing this platform. The distinguishing feature of this system is that it combines the basic measurements with simulations and autonomously learns from the results.

Turbo for materials discovery: Prof. Helge Stein combines high-throughput experiments with artificial intelligence to identify promising battery materials faster and accelerate the development of high-performance energy storage systems. (Photo: A. Heddergott/TUM)

Clever use of digital data resources

Another objective of the TU Munich researchers is to create a decentralized infrastructure and make the valuable research data from battery research accessible and viewable. This could massively speed up the development of battery materials. If these data resources are standardized, an AI can work effectively with them and generally support the research teams. “We therefore want to incorporate the FINALES framework (the abbreviation stands for Fast INtention-Agnostic LEarning Server). It can link up various research institutes throughout Europe without requiring central oversight. Each lab retains control of its own experiments,” explains Stein. The MAP assures optimal exchange of data and smart control of experiments. This improves the efficiency and reproducibility of experiments. The advantage is that the platform covers every relevant step, from formulating and characterizing new electrolytes, through the composition and testing of battery cells, to predicting their operating life. One use

of the system is in optimizing the ionic conductivity of electrolytes and investigating the effect of electrolyte formulations on the operating life of lithium-ion button cells. Stein is convinced: “Digital research data management, the use of AI, and automation will undoubtedly be able to eliminate the bulk of those time-consuming measurements in the lab of the future, leaving much more space for creativity. I think the networking of experiments and data across several sites and labs will take research to an entirely new level because we will suddenly be able to correlate things that previously weren’t visible.”

Automated for better batteries: In Prof. Helge Stein’s laboratories, robots mix various active powders and liquids to create battery pastes, so-called slurries. These are then applied to a copper foil. Conbined with further tests, AI-assisted data evaluation and temperature analyses, the system accelerates the development of high-performance battery materials (Photo: C. Zörlein/e-conversion)

Shaping tomorrow’s world today

The chance to make modern society more sustainable through scientific innovations is a huge goal and motivation for the e-conversion researchers. Together, they address the challenge of developing new materials, mechanisms, and methods that could provide a real impetus in the future. “Now is the time to think big, act boldly – and keep questioning ourselves. Sometimes, you also need to reinvent yourself,” believes Jennifer Rupp. “At the end of the day, what matters to me is that our research makes a difference.” The e-conversion researchers already have a decent track record in that regard. In the first funding period of the Cluster of Excellence nearly 1,300 articles were published (as of July 2025). Seven start-ups were also successfully spun off from e-conversion in wide-ranging fields – from batteries and catalysis to renewable fuels and innovative measurement techniques. The spin-offs demonstrate the horizontal orientation of the Cluster of Excellence across the boundaries of individual technologies. The entire team at e-conversion was delighted with the announcement on May 22, 2025 that the e-conversion success story is set for a new chapter – the next seven-year funding period will start with renewed vigor on January 1, 2026. The priorities for e-conversion 2.0 are to integrate photovoltaics, catalysis, and batteries, conduct research into shared fundamental principles, and drive the development of new applications. Whether in nanoscience or material design, high-throughput screening or AI-assisted learning, the interdisciplinary team of researchers is working very hard at crucial interfaces to smooth the way for the energy transition – and to make green power a dependable partner.